OHT was born to perform heavy lift in the offshore oil and gas business, and has evolved to position itself to lead in the booming offshore renewables sector, including a contract to work in the mammoth Dogger Bank offshore wind build-out. Torgeir Ramstad, CEO, OHT, discusses his company and its role in the growing offshore wind market.

When Torgeir Ramstad took the top post at OHT in 2015, the offshore oil and gas industry was just starting its historic nosedive.

“When I joined the company, I saw great potential in developing the company into new industries,” Ramstad said. “Oil and gas was in its nth downturn, we were looking at alternative industries and quickly came up with offshore wind, primarily because I came from Fred Olsen Windcarrier (as Managing Directory), which is active in turbine installation.”

From there the mold was cast, and by 2020 OHT had more than 50% of its revenues coming from offshore wind deploying its existing fleet. As Ramstad and his team sized up the market and the opportunities, the mission turned to build its portfolio and potential in offshore renewable energy with the aim of exiting the oil and gas sector altogether by 2026, with one exception: sustainable oil and gas decommissioning.

“We will focus our intention on building business in offshore wind, primarily. We will build down our engagement in oil and gas in a deliberate way, and we will eventually decline opportunities in oil and gas if they don’t suit our strategy, because we firmly believe there will be more than enough within offshore wind,” said Ramstad.

THE VALUE PROPOSITION: TRANSPORT & INSTALL

The value proposition that OHT proposes is one shared universally: find a way to do “it” more efficiently. The key difference: “it” – in this regard – is seamlessly transporting mammoth pieces of equipment, thousands of miles in one of the most hostile environs on the planet and dropping it, as they say, on a dime in the bottom of the sea.

Enter Alfa Lift. “We quite quickly came down to a conclusion that we would look at foundation installation primarily, as it is closer to the company’s heritage and expertise,” as well as complementary to its existing transportation fleets, said Ramstad.

While the existing OHT fleet would be an advantage, a newbuild was needed, a mammoth ship that could seamlessly pick up, transport and install the offshore wind foundations, all in one trip over long distances.

“We have a unique concept in Alfa Lift, to install monopiles as a conveyor belt-type machine,” said Ramstad. “We can be faster and more efficient than our competitors; we’re not saying it, our clients tell us that we are the preferred choice in the segment.”

After an investment in design work and development with ‘key partners,’ OHT placed a shipbuilding order in 2018 with China Merchant Heavy Industries in Nantong, China, for Alfa Lift, which will be the world’s largest dedicated foundation installation vessel.

“This was done on speculation,” Ramstad noted, a calculated risk that paid off when 16 months after placing that shipbuilding contract, OHT signed the preferred supplier agreement for Dogger Bank, the world’s largest foundation and installation project for offshore wind. “That puts OHT

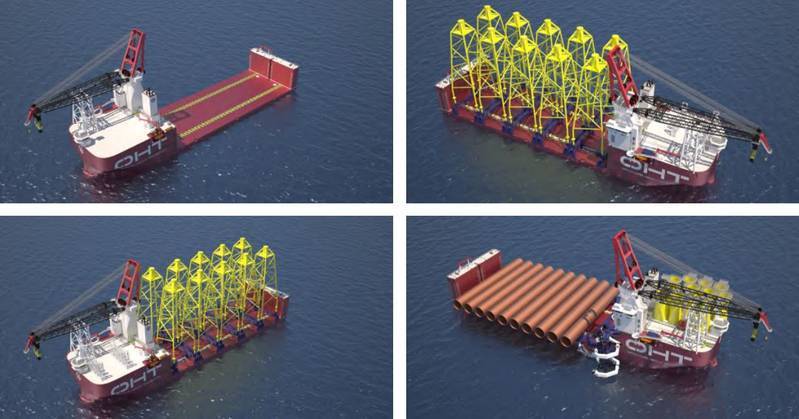

firmly on the map in this industry,” he said.  Alfa Lift Artist's Impression - Credit: OHT

Alfa Lift Artist's Impression - Credit: OHT

“So this whole story was about thinking in terms of high volumes and repetitive tasks,” said Ramstad, with the ‘trick’ being to do it safely, efficiently, correctly, time and again. The traditional means to install the foundations entailed anchoring the ship on the seabed to stabilize the ship and maintain position. But with the pace of installation targeted to one day per monopile, this approach would have been too time-consuming. The solution: installing monopiles in dynamic positioning (DP) mode, something that had not (yet) been done in 2015” (and since then has only recently begun), an approach that saves time and money.

“The whole development of this concept started off with the controls and automation,” said Ramstad. “As I like to say we took the Tesla approach. We didn’t start with the car. We started with the software.”

Central to the success of an operation of this scale in this environment is stability. While many of the challenges to monopile installation in DP mode mirror the challenges found in pipelaying, there is one very important difference: the size and weight of the unit being installed.

“The challenge is to keep the vessel stable enough to achieve very tight tolerances, in terms of verticality for the monopiles,” said Ramstad. “You have to stabilize the monopile, which can be a hundred meters high and weigh maybe two and a half thousand tons. You’re holding it around the center of gravity or even below it … It’s unstable. So we deploy SpaceX algorithms to control it,” the same way SpaceX are able to control the rocket’s landing on a barge in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.”

Alfa Lift is scheduled to join the OHT fleet in early 2022, preparing for the start in Dogger Bank later that year. Meanwhile, in the middle of 2020, while COVID raged and business uncertainty abounded, OHT went from “not being so interested in offshore wind turbine installation” to ordering a Wind Turbine Installation Vessel (WTIV), again, on speculation with China Merchant Heavy Industries, a contract which entered force in November 2020 with a projected delivery in the middle of 2023.

“The end game for us would probably be to see at least two Alfa Lifts and two jacket vessels for the turbine side, accompanied by the transportation vessels that we currently have. And with this, we intend to become a leader in the offshore wind space for transport and installation services.” OHT has scored contracts for the transportation and installation of foundations at Dogger Bank, using the Alfa Lift vessel, currently under construction in China. - File Photo: OHT

OHT has scored contracts for the transportation and installation of foundations at Dogger Bank, using the Alfa Lift vessel, currently under construction in China. - File Photo: OHT

DOGGER BANK

As a newcomer in the installation business, OHT had to then convince one of the most demanding clients in the market that it, as an organization, would be able to step up in regards to capacity, competence, systems, and all that’s required to be a proper contractor, that the concept of its fleet would work the way it’s intended. And in regards to Dogger Bank, there will be little wiggle room for error, as it is a “big scale project, where you’re looking at installing 190 monopiles and transition pieces in the first two phases over a relatively compact schedule,” said Ramstad.

“Alfa Lift efficiently transports and installs over medium distances, regardless of where you end up with your fabrication in Northern Europe. So, all the way down to Northern Spain, Alfa Lift can go to the fabricator, pick up the foundations, and go directly to the wind farm site and install.

Whereas the competitors would rely on separate transportation, intermediate storage, reloading, and then going field to install.”

While Alfa Lift is a large and identifiable manifestation of the OHT proposition, Ramstad said it’s not only about steel, cranes and ships. “That’s just a small part of it,” he said.

“We are a contractor, and as such, you rely on trusting the people that you deal with, and you rely on being able to speak the same language, understand the challenges, and address them in the proper way. I believe that was an equally important aspect that was valid, and eventually led to that contract award (a contract awarded by Equinor, then upon the signing with OHT handed off to SSE, Equinor’s partner, to execute the contract.)

INSIDE ALFA LIFT

As the offshore wind industry grows, ‘feeding the beast’ demands efficiency from foundation manufacture to final install. In this regard, Alfa Lift is both the beast and the buffet line, designed to cut down on trips from the field to the port. “When we went to the ship designer Ulstein in Rotterdam,

we didn’t come with the normal standard metrics – this long, this wide, this deadweight (etc.),” said Ramstad.

“We went and said, “Do you think it’s possible to design a vessel that can install monopiles in one day? And that includes the positioning, the lowering of the monopiles, the piling, the transition piece installation, the bolting and grouting, and the sailing and the transiting and the loading time. So counting the time from [when] you leave port until you’re back fully loaded and ready to leave again.”

What resulted was a creative process to design a ship that is, in a word, big and strong, to streamline the handling of foundations on deck while minimizing transit time from port to field.

“You also need a large stable platform to be more robust in relation to your harsh alignment out in the North Sea; the larger, the better,” said Ramstad. “So, we started off with some iterations and it grew and grew and grew, because the first and the second iterations were too small, and eventually ended up at the sizes we are at now. Next up was designing a cargo handling system to efficiently move and handle the massive piece of unique and valuable cargo … while buffeted by the notoriously rough North Sea.

“We said: ‘In order to mechanize and automate the process of installation, which is actually a serial production or repetitive process, you need to handle things in parallel. You need to not do everything in sequence. You need to also get rid of the people who are exposed on the main deck doing manual operations,” said Ramstad.

In the final concept, they placed a crane upfront on the vessel to free up the space on the main deck, and created a mechanized deck transportation system to bring the foundation components up front towards the crane. Since the crane did not need to cover the entire main deck, it offers a shorter, more robust crane boom … and ultimately a cheaper crane, too.

“With this deck transportation system, we can then feed the crane in the upending position, bringing them from the horizontal to the vertical in an efficient way,” said Ramstad.

“And while installing one monopile, we prepare for the next. And then, of course, in between two monopiles, you do have transition piece, and we decided to carry the transition pieces on the SQ back. That’s normally where you have a big hotel section on the vessel.”

With the main deck being prime real estate for efficient foundation handling, the decision was taken to place the hotel portion of the ship underneath, allowing for much freedom in the placing of other valuable bits of equipment including the 900-ton piling hammer. “The piling hammer is a big beast,” said Torstad, and that sits on the forecastle deck along with the transition pieces.

WHAT’S NEXT?

While the original Alfa Lift is yet to be delivered, thoughts have already turned to Alfa Lift 2, which is currently in basic design. “We have made certain modifications, essentially in relation to an even longer crane boom,” said Ramstad. “This isn’t because of heavier foundations; we are well-covered with what we have on Alfa Lift 1 in that respect. But, if the foundations grow higher or longer, for instance, we see jackets standing on the vessel’s deck soon becoming the limiting factor, in terms of crane height or hook height.”

So the team is looking at a bigger crane with a longer crane boom. “So, probably going from 3,000 tons to 5,000 tons,” said Ramstad. And with a bigger crane comes a slightly longer ship to ensure stability during sailing and install.

“For most people it would look identical. It’s not that big a difference.”

While OHT has invested much time and resources to race ahead in the offshore wind turbine installation game, Ramstad said the trigger for further investment is up to the clients in the form of a contractual commitment. “We have invested close to $600 million on speculation in Alfa Lift and jacket vessels and the organization. Now it’s the client’s turn to commit. We are more than willing to push the button for Alfa Lift 2 or more jack-up vessels, and we have options for three more jack-up vessels as well. But we’re not doing it on speculation.”

“Now clients need to commit to us before we push the button. And, I’m happy to note that several clients and are waking up to that different dynamic in the market, because what they see is this bottleneck from ‘24 onwards. More and more clients [are] coming to us, and probably to our competitors, to secure vessel capacity early.

This is now close to early enough for having enough lead time to actually order and construct a vessel. Whereas before, the lead times for contracts were shorter than the time it takes to build a vessel. But now, it looks like we are approaching a crossing point or even longer lead times for contracts. And therefore, we can sign a commitment for a vessel, push the button with the shipbuilder, get the vessel delivered in time, and perform the project.”

Reviewed by Crude Oil Facilitators

on

21:49

Rating:

Reviewed by Crude Oil Facilitators

on

21:49

Rating:

No comments:

Post a Comment